Burt Barr, Trisha Brown, Robert Rauschenberg, and others at Larry B. Wright Art Productions working on costumes for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s “Set and Reset” (1983), 1983

Trisha Brown and Rauschenberg’s Creative Alliance

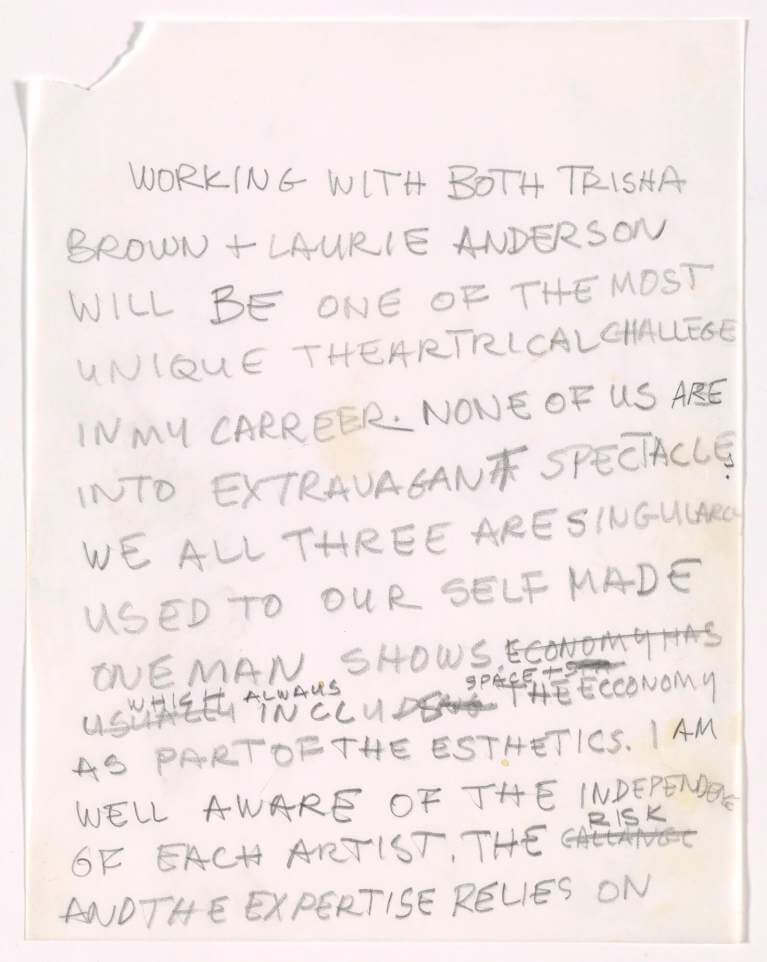

Choreographer Trisha Brown and Rauschenberg were both pivotal figures in the development of Postmodern dance, each pushing the boundaries of form and movement. Collaboration was central to their investigations of the visual and the kinetic, and over the course of five decades, Brown and Rauschenberg deeply influenced one another. Brown spoke of their “uncanny connection” that cemented their life-long friendship and propelled their numerous performance collaborations.

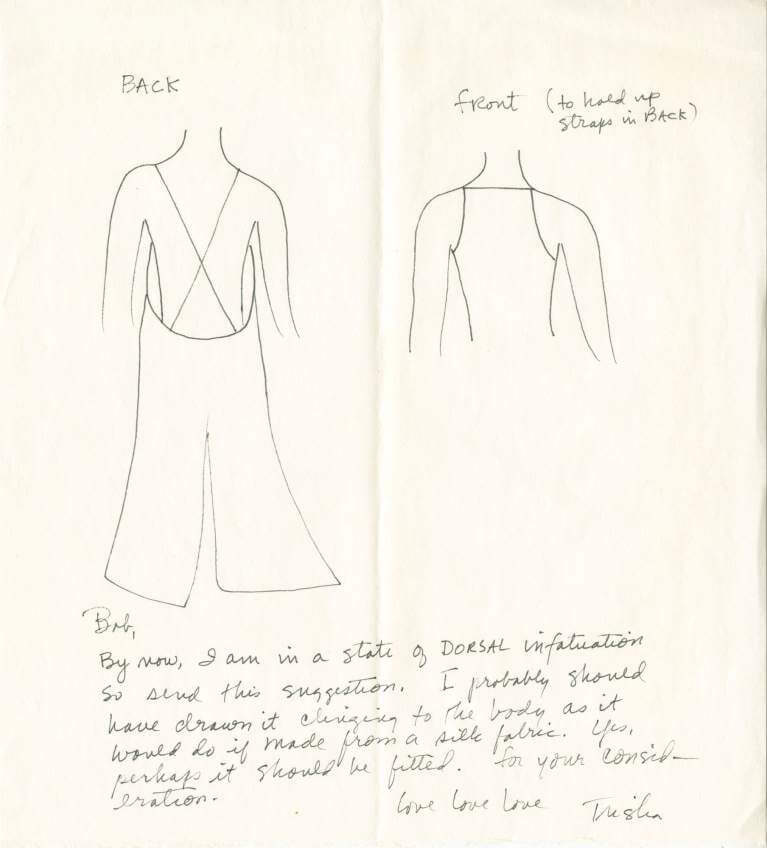

Brown met Rauschenberg during the 1960s, when she was a work-study student at Merce Cunningham’s New York studio. During that time, they both participated in the experimental Judson Dance Theater—often assisting one another and performing in each other’s dances. Following the formation of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in 1970, Brown elected Rauschenberg chairman of the board. Rauschenberg was an ardent advocate for the company throughout his life. Their collaborative relationship was formalized in 1979, when Rauschenberg designed the set and costumes for Brown’s first work for the proscenium stage, the quartet Glacial Decoy (Rauschenberg provided the title).

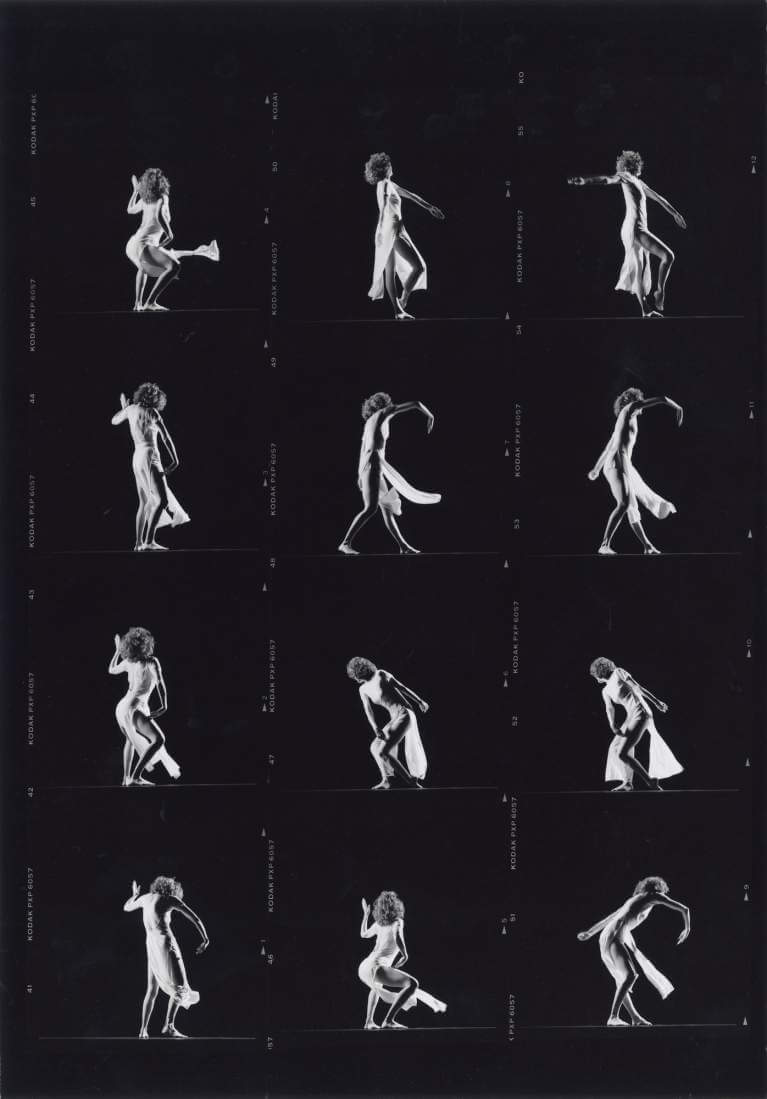

Brown recalls in the 1997 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum retrospective catalogue, “In our collaborations, I was a lightning rod for Bob’s theatrical projections. He described them to me as they occurred to him, often calling in the middle of the night. I would, in turn, picture the descriptions proffered, and in some cases choreograph with the spatial notion of the set he described to me in mind.” It was a collaboration in the truest sense—each drawing inspiration from the other. For Brown’s solo If you couldn’t see me (1994), it was Rauschenberg who suggested the fifty-six-year-old dancer perform without ever facing the audience. While he initially proposed that she perform nude, Rauschenberg worked with Brown to design a form-fitting white costume that exposed her back to emphasize the choreography. Rauschenberg also composed the work’s electronic score.

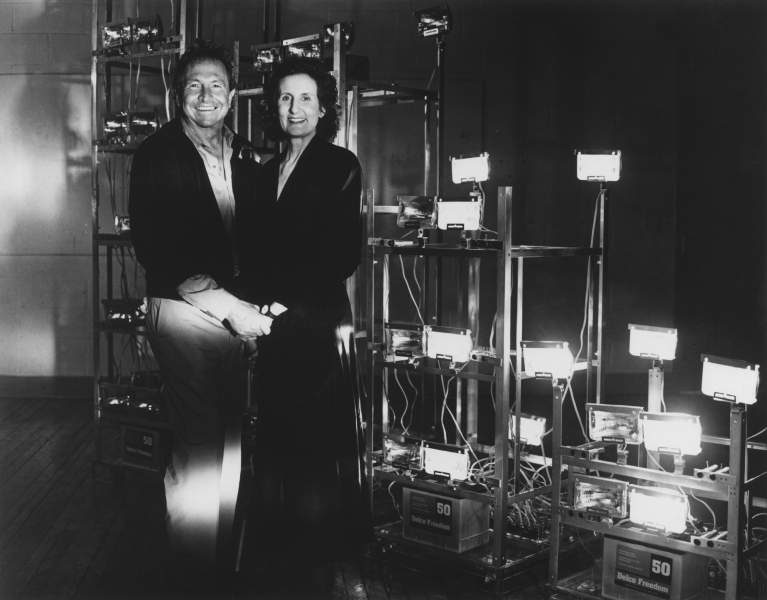

Keenly aware of the practical and budgetary concerns of Brown’s young dance company, Rauschenberg aimed to produce affordable and portable decor—as with the easily transported slide projections of Glacial Decoy. His set for Astral Convertible (1989) was similarly mobile, featuring a “forest” of eight freestanding aluminum towers equipped with sensors that detected movement to trigger light and sound, created with engineers Per Biorn and Billy Klüver. The design satisfied Brown’s request for a set that could be used outdoors, realized for Astral Converted (50") (1991), which reused the towers for a performance on the steps of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

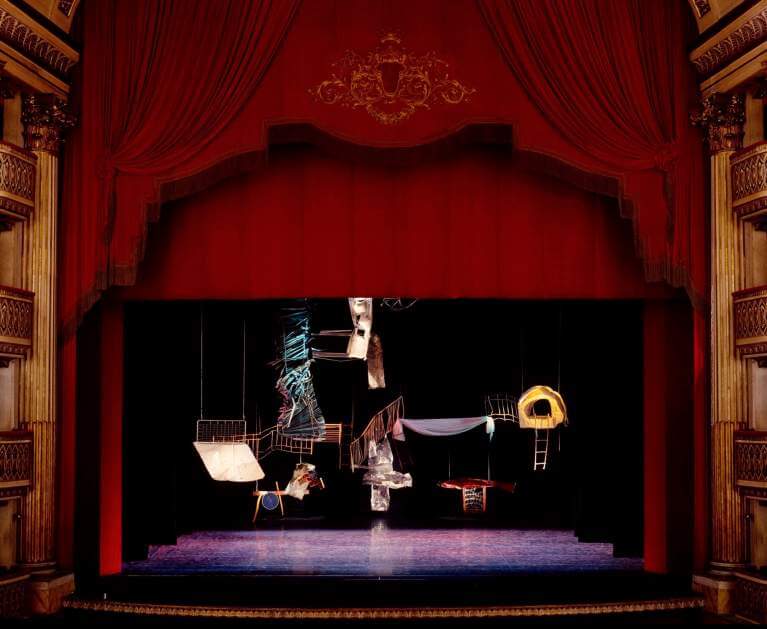

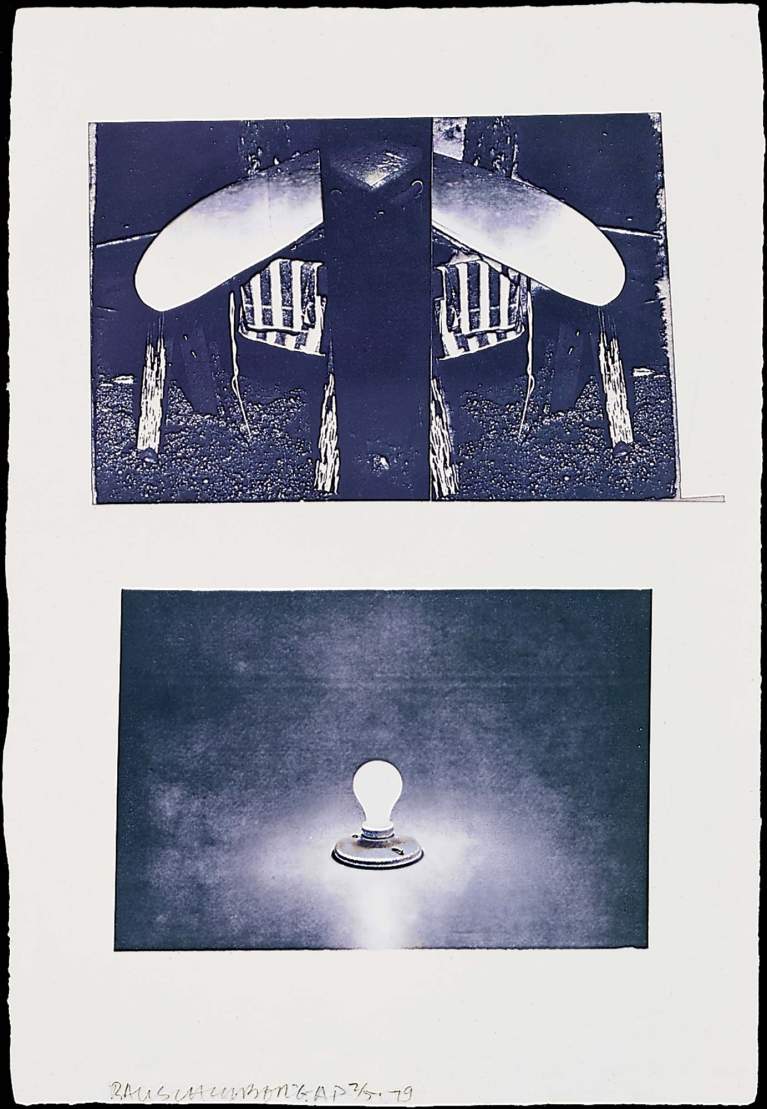

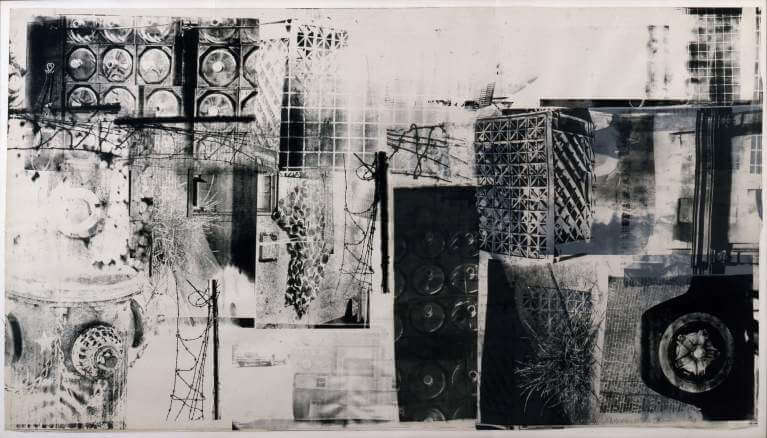

Several of Rauschenberg’s other collaborations with Brown correlate with his own artistic practice. The set for Glacial Decoy was composed of hundreds of Rauschenberg’s black-and-white photographs projected on four large screens, rekindling his passion for the medium. The images, taken in Fort Myers, Florida, can be found in two concurrent print series by the artist: Glacial Decoy Series (1979–80) and Rookery Mounds (1979). Glacial Decoy photographs also appear in painting series throughout the following decade. When silkscreening his black-and-white photographs onto the costumes for Set and Reset (1983), the images bled through the fabric to drop cloths underneath, inspiring the Salvage series (1983–85). In 1987, Rauschenberg’s emergency set for Brown’s Lateral Pass (1985) at the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, utilized scrap metal and fabric to create temporary hanging sculptures for the stage. He reworked pieces of the set to make Gluts (1986–89/1991–94), referring to this group as Neapolitan Gluts.

Brown and Rauschenberg maintained a remarkable creative dialogue, mutually influencing one another for nearly half a century until Rauschenberg’s death in 2008.

Jennifer Sarathy, Research Assistant, 2017