Artist

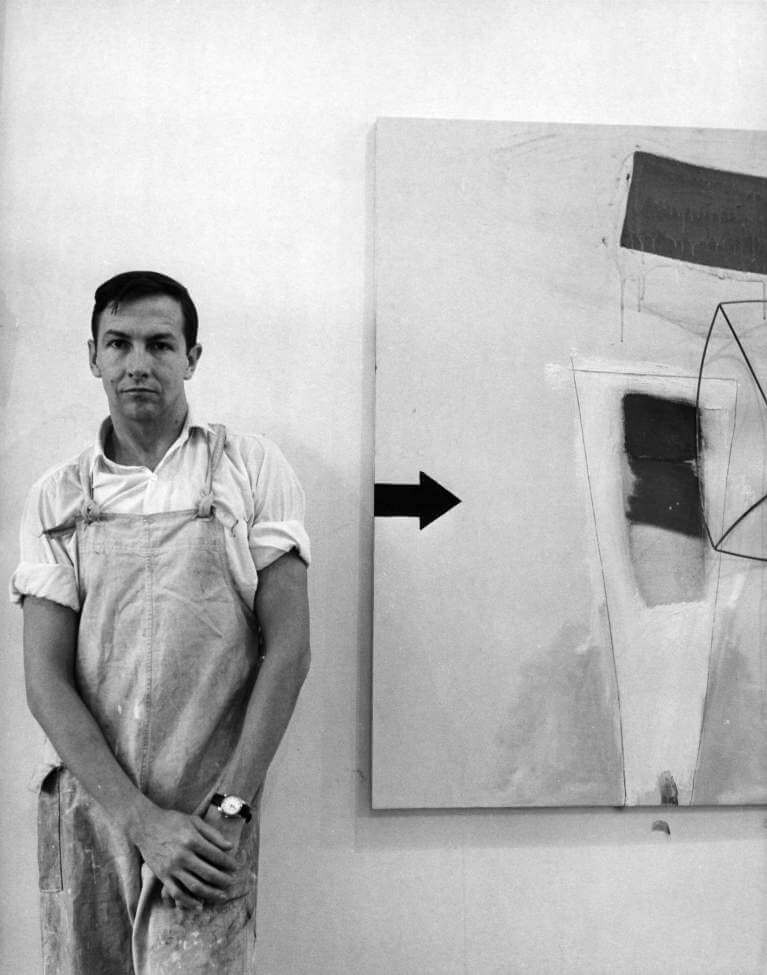

Rauschenberg with Stripper (1962) in his Broadway studio, New York, ca. 1962

Overview: Life and Art

Robert Rauschenberg’s art has always been one of thoughtful inclusion. Working in a wide range of subjects, styles, materials, and techniques, Rauschenberg has been called a forerunner of essentially every postwar movement since Abstract Expressionism. He remained, however, independent of any particular affiliation. At the time that he began making art in the late 1940s and early 1950s, his belief that “painting relates to both art and life” presented a direct challenge to the prevalent modernist aesthetic.

The celebrated Combines, begun in the mid-1950s, brought real-world images and objects into the realm of abstract painting and countered sanctioned divisions between painting and sculpture. These works established the artist’s ongoing dialogue between mediums, between the handmade and the readymade, and between the gestural brushstroke and the mechanically reproduced image. Rauschenberg’s lifelong commitment to collaboration—with performers, printmakers, engineers, writers, artists, and artisans from around the world—is a further manifestation of his expansive artistic philosophy.

This text and the following chapter texts are adapted from an essay written by Julia Blaut, “Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective,” @Guggenheim (Fall 1997).

Quiet House—Black Mountain, 1949

Early Works, 1948-54

Beginning in 1948, Rauschenberg attended Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina. His work at Black Mountain reveals many of the principal themes that recur throughout his oeuvre: sequences and progressions through time, grid formats, doubling and mirroring, and a sense of the human scale. During these formative years Rauschenberg used a wide range of art-making mediums, including printmaking, painting, photography, drawing (both conventional and experimental techniques), and sculpture. As would become his hallmark, he often used them in combination, blurring conventional distinctions between artistic categories. Collaboration with other artists would also remain an impetus throughout his career, and his early work with composer John Cage and dancer/choreographer Merce Cunningham inspired him to engage in conceptual modes and performance.

Having settled in New York in fall 1949, Rauschenberg was introduced to the work of the Abstract Expressionists and began to incorporate their free brushwork into his own paintings. In the art made both at Black Mountain College and in New York between 1951 and 1953, Rauschenberg expanded on the abstract idiom with the inclusion of recognizable images and materials taken from his immediate environment. He impressed pebbles into the dark pigment of his Night Blooming paintings (1951); the uninflected White Paintings (1951) became screens for light and shadow, responding to the conditions around them; and newspaper collage formed the ground of the series of Black Paintings (1951–53).

Rauschenberg’s collages and sculptures made in 1952–53 while traveling with artist Cy Twombly in Europe and North Africa, introduce his method of combining disparate subjects and contain many of his enduring motifs: body parts, modes of transportation, fine art reproductions, lettering, and diagrams. The small, fetishistic assemblages made in Italy from found materials, as well as the Elemental Sculptures and the Red Paintings begun on his return to New York in 1953, were laboratories for the later Combines.

Untitled [Egan Gallery installation shot], 1954. Photo: Robert Rauschenberg

Expanding Career, 1954–69

For Rauschenberg there was a natural progression from the Red Paintings to the Combines, as two-dimensional collage and eventually three-dimensional objects came to the fore. By summer 1954, Rauschenberg had made the first, fully realized Combine, eliminating all distinctions between painting and sculpture. Expanding on Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade, Rauschenberg imbued new significance to such ordinary objects as a patchwork quilt or an automobile tire by combining unrelated items and incorporating them into the context of art. When Rauschenberg first exhibited the Red Paintings and Combines at the Egan Gallery, New York, in December 1954, critics were baffled by the works, which challenged existing definitions of art.

Less than a decade later, however, Rauschenberg’s reputation as the leading artist of his generation was established following his first solo exhibition held in 1963 at the Jewish Museum, New York, and his award the following year of the International Grand Prize in Painting at the Venice Biennale. Of the works by Rauschenberg shown at the U.S. Pavilion were many of his now-celebrated Combines, including Bed (1955), as well as several paintings from a series the artist began in fall 1962, in which he used commercially produced silkscreens based on media sources and his own photographs.

Rauschenberg’s use of a commercial means of reproduction and his focus on media subjects in this series led art critics to identify him with the Pop art movement that had recently emerged on the New York art scene in 1962. In comparison with the often coolly executed paintings of the Pop artists, however, Rauschenberg’s works are emphatically gestural and handmade. The silkscreen paintings have an expressive quality that results from their hand-painted areas, the collage-like overlays of photographic images, and the intentional slippage and irregularities, which the artist allowed to remain uncorrected during the screening process.

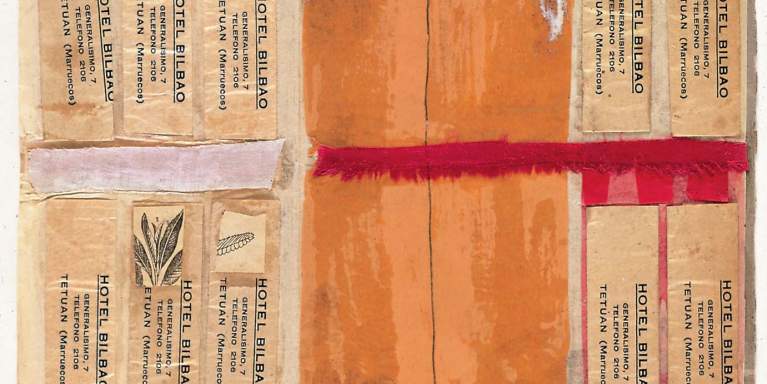

Untitled (Hotel Bilbao), ca. 1952

Works on Paper, Photographs, and Editions, 1952-2008

Works on paper and photography comprise some of Rauschenberg’s most significant early works: the series of collages made on Italian shirtboards (ca. 1952); photographs taken in Europe and North Africa during his travels with artist Cy Twomby in 1952–53; and various types of monoprints, including the blueprints he made with his wife at the time, Susan Weil (ca. 1950), and the Automobile Tire Print that he made with John Cage in 1953. It was not until the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, that the found image became paramount in Rauschenberg’s visual vocabulary. Reproductions from newspapers and magazines were incorporated into his drawings and prints as he perfected techniques of solvent transfer and lithography. The transfer drawings (largely produced simultaneously with the later Combines) brought the element of collage onto a two-dimensional plane; found images were now continuous with the picture surface and were mixed with freely drawn and painted areas.

By 1962, Rauschenberg was exploring the transfer technique in his prints. He made his first lithograph at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) in West Islip, New York; and in 1963, he won the Grand Prize at the prestigious International Exhibition of Prints in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. Printmaking remained central to Rauschenberg’s art-making practice due to the medium’s inherent reproducibility and the wide range of effects it enabled him to achieve.

Rauschenberg’s early interest in photography was renewed in 1979 with his first collaboration with the Trisha Brown Dance Company. His set design for Glacial Decoy (1979) was comprised of projections of his own black-and-white photographs. Several photography projects followed, including In + Out of City Limits (1979–81) and the Photem Series (1981/1991); both reveal Rauschenberg’s preference for common, street-level subjects. Until he could no longer hold a camera after suffering a stroke in 2002, the photographic images incorporated into Rauschenberg’s work in all mediums had—since 1979—been drawn exclusively from his own photographs.

Rauschenberg and engineer Billy Klüver working on Oracle (1962–65) in Rauschenberg’s Broadway studio, New York, 1965. Photo: Larry Morris/The New York Times/Redux Pictures

Art and Technology, 1959–98

Among the collaborative ventures that brought Rauschenberg emphatically outside the confines of his studio were his experimental works in art and technology. The artist’s interest in bringing technology into his art was already evident in some of the early Combines that integrated working appliances, such as radios, fans, electric lights, and clocks, allowing sound, motion, light, and the passage of time to quite literally be incorporated into his art.

Through his participation in the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely’s kinetic environment, Homage to New York in 1960, Rauschenberg began working with Bell Laboratories research scientist, Billy Klüver. In collaboration with Klüver, Rauschenberg realized some of his most ambitious technological works, including the sound-producing sculptural environment, Oracle (1962–65), as well as Soundings (1968), a monumental light installation responsive to ambient sound. Both works were meant to be experienced by the audience spatially and appeal to the senses beyond the purely visual.

In 1966, Rauschenberg and Klüver, together with artist Robert Whitman and engineer Fred Waldhauer, founded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), New York, an organization that sought to make technology accessible to artists by arranging collaborations with engineers. In the same year and due to their interest in the potential application of technology for theater, they produced 9 Evenings: Theater & Engineering, an event that brought together visual artists, dancers, choreographers, scientists, and engineers, which resulted in technologically sophisticated performance works.

While Rauschenberg’s preoccupation with technology-based art reached its height during the 1960s, the artist would continue to periodically utilize technology in his art making through the 1990s. Among his later technology-based works was the series Eco-Echo (1993). Made following his attendance at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the sonar-activated windmills referred to the artist’s environmental concerns and his interest in ecologically responsible sources of power.

Rauschenberg performing his piece Pelican (1963), First New York Theater Rally, former CBS studio, Broadway and Eighty-first Street, New York, May 1965. Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Performance, Choreography, and Stage Design, 1952–2007

Performance, in its many manifestations, was at the core of much of Rauschenberg’s artistic output. His involvement with performance began when he participated with choreographer Merce Cunningham in composer John Cage’s Theatre Piece #1 (originally an untitled work that is sometimes referred to as the first Happening) at Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina, in 1952. Throughout his career, Rauschenberg not only designed sets, costumes, and lighting for Cunningham and other choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Paul Taylor, but he also performed and choreographed his own works. The theatrical element was not limited to live performance but was often an integral part of his nonperformance works, including the integration of sound in an Elemental Sculpture that incorporates a hidden sound; the passage of time in a Combine that includes a working clock; or the incorpation of motion in a technology piece that churns mud.

As was true of much of Rauschenberg’s work, the lines were intentionally blurred between his performance work and his work in other media. For example, a freestanding Combine, Minutiae (1954), was created as a stage set for a Cunningham performance; while his First Time Painting (1961), another Combine, was made by the artist while on stage at the American Embassy in Paris as part of the performance Homage to David Tudor. When on tour with Cunningham, Rauschenberg created scenery by spontaneously using found objects and sounds, as he developed the concept of “live décor,” or scenery generated by human activity.

The artistic dialogue with Cage and Cunningham positioned Rauschenberg at the cutting edge of postmodern dance. His involvement in the early 1960s with Judson Dance Theater, New York, an experimental collective that included dancers as well as visual artists, resulted in performances free of narrative, emphasizing instead the purity of movement—sometimes conventionally dance-like, but also mundane movements, allowing untrained performers to participate side by side with professional dancers. Throughout his career, Rauschenberg found collaboration—either with artists working in a broad range of media and from around the globe or with engineers in the development of works that combined art and technology—to be a productive means for pushing the boundaries of conventional art making.

National Spinning / Red / Spring (Cardboard), 1971

Mid-Career, 1970s–1980s

With his move in 1970 from New York to Captiva Island, off the Gulf Coast of Florida, Rauschenberg cleared his palette. Retreating from urban imagery, he now favored a more abstract idiom and the use of natural fibers, such as fabric and paper. The Cardboards (1971–72) and the Venetians (1972–73) reveal his fascination with the inherent color, texture, and history of found materials. The beautiful and disparate effects of fabrics, ranging from cotton to satin, are explored in the Hoarfrosts (1974–76) and Jammers (1975–76). Collaborations at paper mills in France and India resulted in works where paper pulp was elevated to an art form.

A mid-career retrospective was mounted in 1976 by the National Collection of Fine Arts [now the Smithsonia Museum of American Art], Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., when Rauschenberg was selected to honor the American Bicentennial. Having the opportunity to reexamine his early work, Rauschenberg returned to past concerns. His Spreads (1975–83) and Scales (1977–81) incorporate transferred and screened images as well as assemblage, sometimes in room-scale installations.

During the 1980s, Rauschenberg undertook two long-term projects. The first, The ¼ Mile or 2 Furlong Piece, was begun in 1981, and completed in 1998. This multi-part work consists of 191 components and spans more than a quarter mile. Retrospective in character, this piece is replete with references to his life and art.

The second project—Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI)—was the most tangible expression of Rauschenberg’s belief in the power of art and artistic collaboration to bring about social change on an international level. Traveling around the world for ROCI, Rauschenberg’s exploration of diverse cultures and local art-making practices gave rise to an extraordinarily diverse body of work. The catalyst for the metal painting and sculpture series was ROCI CHILE, where he painted and screened on copper in 1985. Over the next decade, Rauschenberg explored the use of metal as a support for paint, tarnishes, enamel, and screenprinted images in several subsequent series, such as Urban Bourbons (1988–96) and Night Shades (1991). The Gluts, begun in 1986, are made from scrap metal objects, including gas-station signs and automobile parts, which often mask the original identities when transformed into wall and freestanding sculptures.

Rauschenberg working on Scripture (1974) for Rauschenberg in Israel exhibition at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1974. Works in background are Scripture I and two untitled works (all 1974). Photo: Nir Bareket

International Collaborations, 1973–95

Rauschenberg’s belief in the power of art as a catalyst for positive social change was at the heart of his participation in numerous international projects. In the 1970s and early 1980s he collaborated with papermakers in France, India, and China, as well as with artisans at a ceramic factory in Japan. Through his travels, Rauschenberg collected a store of materials to use when he returned to his Captiva studio in Florida, including photographs, local objects, textiles, and printed matter. The resulting works were inevitably informed by his new understanding for another culture, yet the admixture of imagery and materials was distinctly Rauschenbergian.

Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) became the artist’s primary preoccupation between 1984 and 1991 and was a tangible expression of his long-term commitment to human rights and to the freedom of artistic expression. Rauschenberg financed the ROCI project and traveled to ten countries, exploring diverse cultures and local art-making practices. Mounting an exhibition of his work in each country, often where artistic experimentation had been suppressed, his purpose was to spark a dialogue and to achieve a mutual understanding through the creative process.

Tribute (Anagram), 1995

Late Work, 1992–2008

In his late work, Rauschenberg continued to approach his art with the spirit of invention and with the quest for new material and new technology that was characteristic of his work throughout his career. Beginning in 1992, Rauschenberg used an Iris printer to make digital color prints of his photographs. It is this technology that allowed for the high-resolution images and luminous hues in the large-scale works on paper, the Waterworks (1992–95) and Anagrams (1995–97). In 1996, he transferred the Iris prints to wet plaster in the Arcadian Retreats (a fresco series that provided him with an entirely new avenue of exploration) and onto polylaminate panels in his last three bodies of work, Short Stories (2000–2002), Scenarios (2002–06), and finally, Runts (2006–08).

Despite his use of new materials and methods, much of Rauschenberg’s later work looks back at his earlier art and is autobiographical in nature. With the artist’s retrospective exhibition organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1997, which traveled to venues in the United States and Europe, the artist had the opportunity to view the full scope of what at that point had been a fifty-year career. During that same year, Rauschenberg worked in glass for the first time, creating sculptures of his iconic subjects: a tire, a pillow, a shovel, and a broom, each dignified by a silver platform. His monumental Mirthday Man (1997) from the Anagram (A Pun) series made on the occasion of his seventy-second birthday, includes a reproduction of the life-size X-ray of the artist first used in the print Booster (1967), while the imagery in the editioned Ruminations series (2000) refers to important moments and figures in the artist’s early life.

Following a stroke in 2002 that leaves his right hand partially paralyzed, the artist continued to work, undeterred, but now with his left hand. During this final decade, he continued his collaborations with performers and printmakers and his commitment to humanitarian causes.