1950-59

1953

January 11–February 7: Participates in 2nd Annual Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture, successor to the Ninth Street Show of 1951, Stable Gallery, New York. One of Rauschenberg’s Black Paintings, submitted by Jack Tworkov, who had been storing it, is exhibited.

February: Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly return to Rome from Africa by way of Spain.

March: In Rome, visits artist Alberto Burri, who is ill, and offers him a healing fetish, a small box construction, as a get-well gift. Burri gives a small work to Rauschenberg in return, Senza Titulo (1952), made of paint and fabric collage on Masonite.

March 3–10: First solo exhibition in Europe, Scatole e Feticci Personali, Galleria dell’Obelisco, Rome, a gallery that exhibits works by such contemporary Italian artists as Afro and Burri. To both Rauschenberg’s and the gallery owner’s amazement, some of the boxes and hanging wall pieces are sold, and Rauschenberg earns enough money to travel back to New York. In a statement for the exhibition, Rauschenberg writes, “Many of the boxes are a third- dimensional poem of one work: White.”11 The show travels as Scatole e Costruzioni Contemplative di Bob Rauschenberg to Galleria d’Arte Contemporanea, Florence, where Twombly’s exhibition Mostra de Arazzi di Cy Twombly opens on the same day.

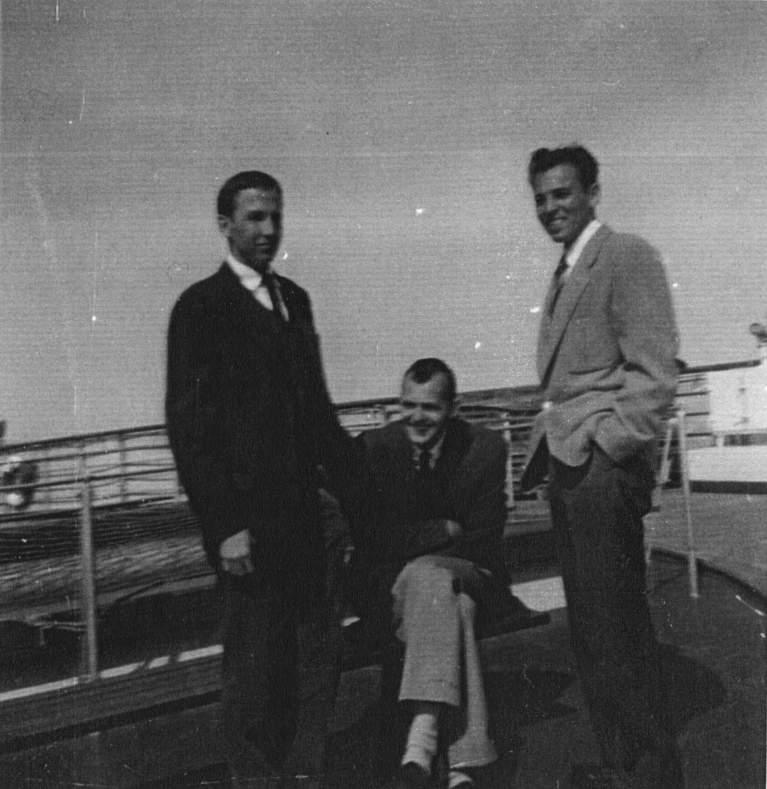

April: Returns to New York on the SS Andrea Doria and moves into a loft at 61 Fulton Street in downtown Manhattan. Rauschenberg is one of the first New York artists to establish a studio loft in a formerly industrial building. Cage, Cunningham, Morton Feldman, and Philip Guston live in a nearby loft building. Photographs document that Twombly occasionally worked in Rauschenberg’s studio.

Between April 15 and May 9: Visits Dada 1916–1923, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, curated by Marcel Duchamp, who also designs the poster.

Spring–summer: Completes the last of the Black Paintings, begun at Black Mountain College in 1951, and begins the Elemental Sculpture series (1953/1959), made of wood, stones, twine, steel spikes, and other materials found in the Fulton Street neighborhood. Also at the Fulton Street studio, Rauschenberg makes the first of the Gold Painting series (1953–ca. 1960), in which he applies gold leaf to a ground of newsprint, paper, on wooden supports. These are small works with highly tactile surfaces. Rauschenberg will return to the Gold Painting series later in the decade. The earliest Gold Paintings were created as part of the series of elemental paintings (ca. 1953), a term later coined to refer to artist’s work made with unconventional art materials including dirt, grass, gold, lead, clay, mold, and tissue paper, and often contained in wooden frames.12 Cage brings Feldman to Rauschenberg’s studio, where he buys a Black Painting for the amount of money in his pocket: $16 and some change. Continues to freelance window design for Gene Moore at Bonwit Teller, New York as a means of support.

Summer: Merce Cunningham Dance Company is formed during summer residency at Black Mountain College. The original dancers of the small company are Carolyn Brown, Remy Charlip, Judith Dunn, Viola Farber, Jo Anne Melsher, Marianne Preger, and Paul Taylor. Cage is musical director.

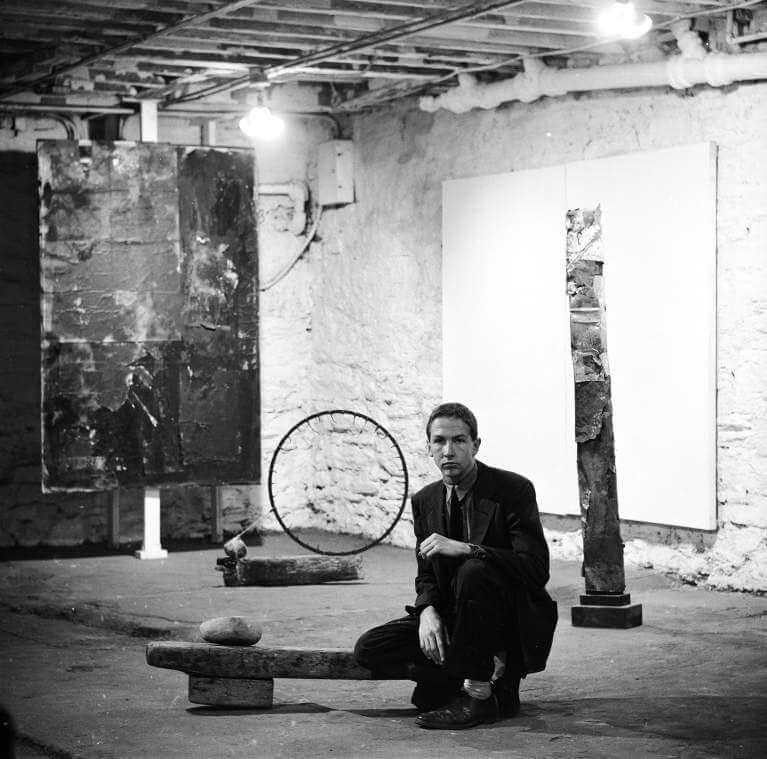

Eleanor Ward, owner of Stable Gallery, New York, is brought to Rauschenberg’s Fulton Street studio by painter Nicolas Carone. Ward offers Rauschenberg and Twombly a joint exhibition. Rauschenberg and Twombly clean out the basement of the gallery, a former horse stable, to exhibit their works there, as well as in the first-floor galleries. Rauschenberg will go on to work as a handyman and janitor for the gallery.

September 15–October 3: Concurrent exhibition of works by Rauschenberg and Twombly, Stable Gallery, New York. Rauschenberg exhibits two White Paintings and a selection of Black Paintings, as well as Elemental Sculptures.13 Cage writes a statement on the White Paintings for the exhibition: To whom/No subject/No image/No taste/No object/No beauty/No message/No talent/No technique (no why)/No idea/No intention/No art/No object/No feeling/No black/No white (no and)/After careful consideration, I have come to the conclusion that there is nothing in these paintings that could not be changed, that they can be seen in any light and are not destroyed by the action of shadows./Hallelujah! the blind can see again; the water’s fine.14 The show elicits six, mostly negative, reviews in the New York press and in art journals. None of the works are sold until the final day of the exhibition, when friends Carolyn and Earle Brown, a dancer and composer respectively, purchase a Black Painting for a total sum of $26.30—the amount of money in their pockets from cashing a telephone-deposit refund check.

Fall: Creates Automobile Tire Print and Erased de Kooning Drawing (both 1953). The first work is made with the collaboration of Cage and his Model A Ford on a quiet Sunday morning outside the Fulton Street studio. Cage slowly drives the car while Rauschenberg applies black house paint to the rear tire that also rolls down a long strip of paper, approximately twenty-two feet in length, which Rauschenberg has made by gluing together twenty sheets of paper. The work can be partially displayed like a rolled Japanese scroll. To create Erased de Kooning Drawing, Rauschenberg asks Willem de Kooning for a drawing to be erased and presented as Rauschenberg’s own work; de Kooning offers him a drawing made from pencil, crayon, and possibly ink, which will present a serious challenge. Spends almost a month erasing the work on which traces of de Kooning’s original marks still remain. Erased de Kooning Drawing will be exhibited for the first time in a group exhibition at Poindexter Gallery, New York (December 19, 1955–January 7, 1956),15 and then not again until 1964 at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Late fall: Begins Red Paintings (1953–54) that he will continue to work on until early summer 1954. Rauschenberg welcomes the challenge to explore what he regards to be “the most difficult color” with which to work.16 Like the Black Paintings completed at Fulton Street, the early Red Paintings are painted on canvases that incorporate newspapers and patterned fabrics as grounds. Heavily painted pigments are applied to the canvas in a variety of ways, including brushstrokes, drips, impasto, and color squeezed directly from the tube. As he continues to develop the series the following summer, Rauschenberg will begin to incorporate found objects, anticipating the three-dimensionality of the Combine series to follow.

Late fall: Introduced to Jasper Johns by Suzi Gablik (a painter friend from Black Mountain College and later an art critic) on a New York street corner near Marboro Books, an art bookstore where Johns works.

- 11. Rauschenberg’s statement is reproduced in Hopps, p. 32.

- 12. At this time, the known extant works from this group are: nine gold; one lead; one dirt; and two clay paintings, one of which was remade by the artist as a replacement for the 1953 original belonging to John Cage that had been borrowed for exhibition but was never returned.

- 13. Ten of the works, which have been lost or destroyed, are documented in photographs of the exhibition made for Life, although they were never published in the magazine.

- 14. John Cage’s statement, distributed as a handout in the gallery, is quoted in its entirety in Emily Genauer, “Art and Artists: Musings on Miscellany,” New York Herald Tribune, Dec. 27, 1953, sec. 4, p. 6.

- 15. The 1955–56 exhibition of the work is discussed in Sarah Roberts, “Erased de Kooning Drawing,” Rauschenberg Research Project (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, July 2013). Accessed Sept. 15, 2014. http://www.sfmoma.org/explore/collection/artwork/25846/essay/erased_de_kooning_drawing. The exhibition dates are confirmed by the Estate of Jack Tworkov website, where the exhibition announcement is also available. Accessed Sept. 15, 2014. http://jacktworkov.com/exhibitions/index.php?.

- 16. Quoted in Barbara Rose, Rauschenberg (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), p. 53.

Rauschenberg (left) and Cy Twombly (seated) returning from Italy to New York City aboard SS Andrea Doria with fellow passenger Kurt Osinsky (right), April 1953. Photo: Edith Osinsky

Rauschenberg (left) and Cy Twombly (seated) returning from Italy to New York City aboard SS Andrea Doria with fellow passenger Kurt Osinsky (right), April 1953. Photo: Edith Osinsky

Rauschenberg at Robert Rauschenberg: Paintings and Sculpture, Stable Gallery, New York, fall 1953. Photo: Allan Grant/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Rauschenberg at Robert Rauschenberg: Paintings and Sculpture, Stable Gallery, New York, fall 1953. Photo: Allan Grant/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images