Yvonne Rainer

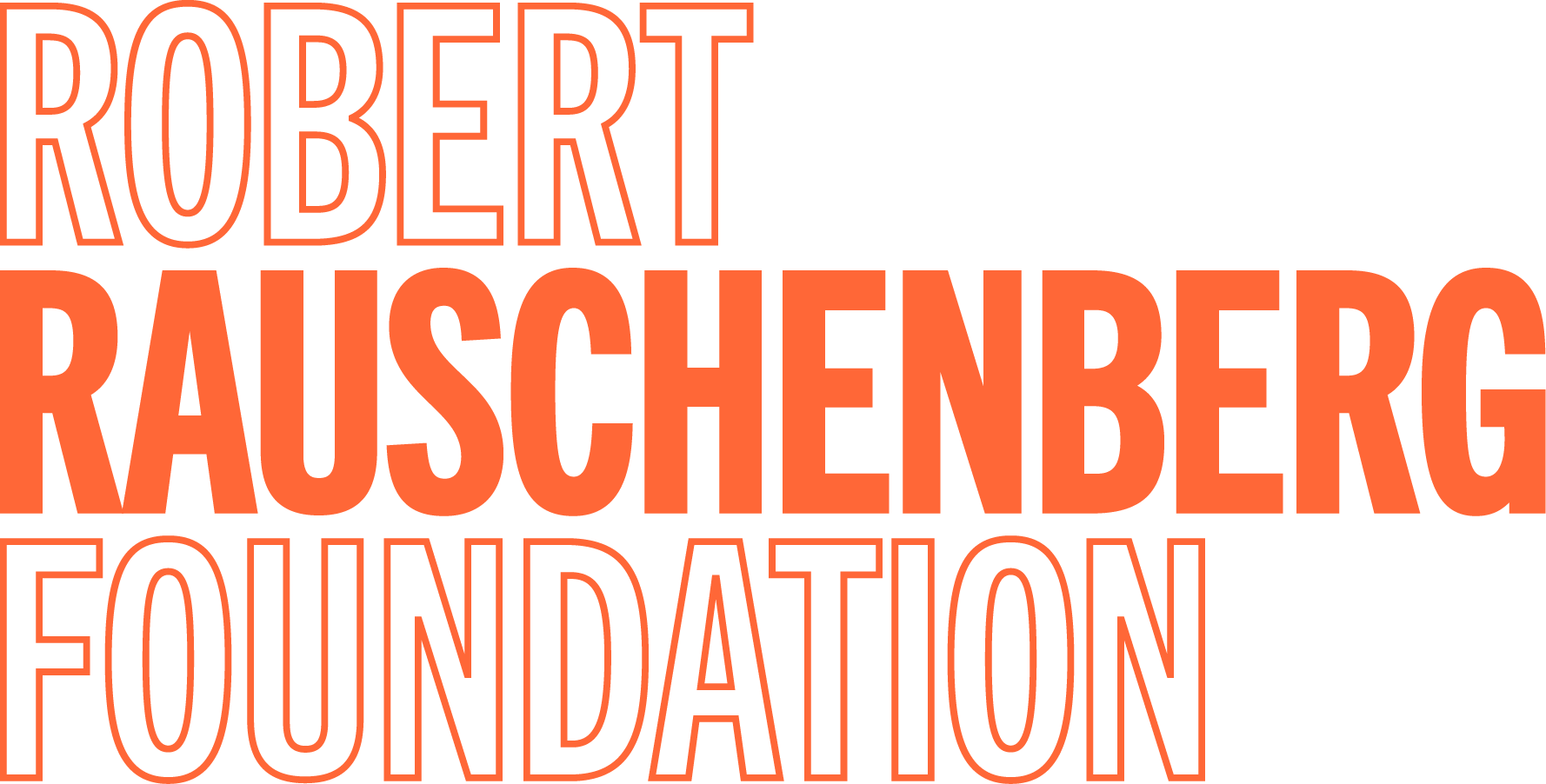

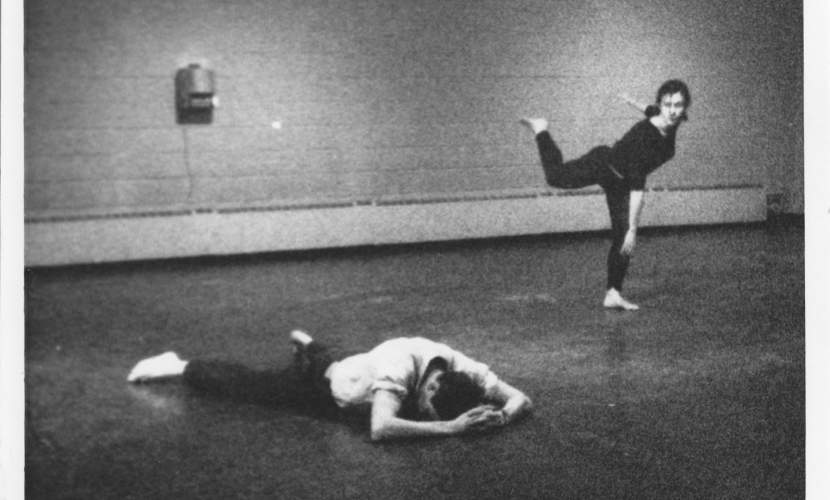

Yvonne Rainer is an accomplished choreographer, dancer, and filmmaker. In 1962 she cofounded the highly innovative Judson Dance Theater that included Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Simone Forti, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, and Rauschenberg, among others. During the years of the Judson Dance Theater (1962–64), Rauschenberg provided technical support for several of Rainer’s performances. The two artists also danced together in numerous programs between 1964 and 1965. In 1967 Rainer performed in Rauschenberg’s Outskirts and Urban Round at the Loeb Student Center, New York University.

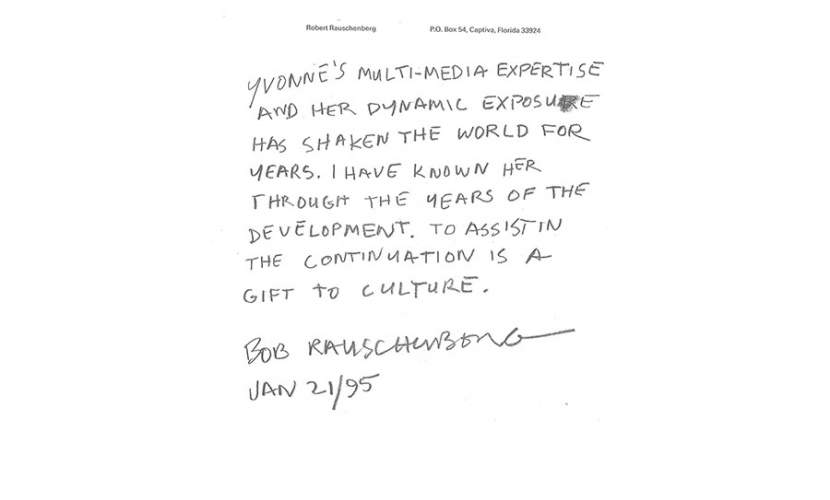

Beginning in 1972 Rainer shifted her focus to filmmaking and produced seven experimental feature-length films. In 2000 Rainer returned to dance with After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, a commission for Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project. Rainer’s pieces have been performed worldwide, and retrospectives of her work have been shown internationally. Her memoir, Feelings Are Facts: A Life, was published by MIT Press in 2006 and a selection of her poetry was published in 2011 by Badlands Unlimited.

Excerpt from Interview with Yvonne Rainer by Alessandra Nicifero, 2014

Rainer: [recalling 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, 1966] My proposed piece was very elaborate, where there would be minimalist actions on the ground and in the air would be remotely-programmed events, like big plastic balls traveling across the space. From a 50-foot ceiling these spidery slats would descend at a certain point. I remember Rauschenberg’s event was a tennis match between two people and every time the ball was hit a light would go off until it was dark [Open Score, 1966]. Deborah Hay had people on moving platforms [Solo, 1966]. Each of us was assigned our own scientist technician to work with. I forget the name of my scientist [note: Per Biorn] but he had me running down to Lafayette Street and getting all kinds of apparatus, technical things that he needed to program my events.

There were a lot of mishaps in some of these collaborations. Cage had all this equipment and we were all splicing wires for him for a week. This big platform ran over and cut some of these wires and it all had to happen again. The first night of my performance—I shared the evening with Cage—none of my events happened. They had been programmed backwards or something. Nothing was working and I remember I was up on a balcony, and Bob crawled on all fours and said, “Nothing is happening. What shall we do?” I don’t know. Then I was supposed to be giving directions to my performers. I said, “Well, let them do whatever they want,” moving all these objects around, from a piece of paper to a mattress to free weights. It was a landscape of objects.

Nicifero: And Bob Rauschenberg was one of the performers for your—

Rainer: No. He wasn’t. I had about ten or twelve performers. But he was there every night, like a troubleshooter or assistant, doing whatever needed to be done. I remember that first night, the events had been advertised as the eighth wonder of the world and what did the audience see? A tennis match where the lights kept going out, or my event where people, my performers, were standing around waiting for instructions [laughs], which didn’t happen, and they started to applaud with displeasure.

[ . . . ]

Oh, I didn’t mention. He performed in a forty-five-minute work of mine in 1965 called Parts of Some Sextets with twelve mattresses and ten performers. He was one of the performers. He came to all the rehearsals, which were twice a week for a month or two. He was gung ho to be involved and was not at all a prima donna or anything like that.

Nicifero: He’s always described as a hard worker and always very engaged in what he was doing.

Rainer: Yes, when he committed himself, he worked. [Pauses] He was a very handsome young man. On that note—

[Laughter]

Nicifero: Okay. Thank you.