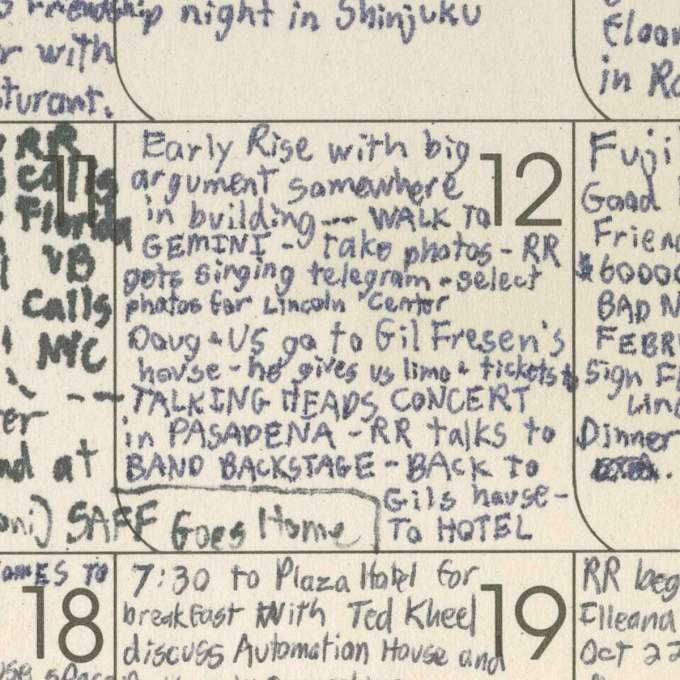

Rauschenberg’s 1982 calendar, August page (detail)

All the Small Things: Receipts and Ephemera in the RRF Archives

At the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, sometimes the smallest items open the biggest doors. As researchers’ primary point of access to the most comprehensive trove of documentation about the artist, the Robert Rauschenberg Papers provide a source of endless intrigue and potential. This collection, the largest in the Foundation Archives, comprises Rauschenberg’s studio records and personal papers, documenting both his artistic practice and life within and outside of the studio, from Port Arthur, Texas; to Black Mountain College; New York; Captiva, Florida; and travels across the globe.

The abundance and diversity of archival materials (correspondence, writings, sketches, photographs, ephemera, etc.) quickly dispels any temptation to define the artist’s archive by what it is not (artwork), promising new discoveries and boundless inspiration to the curious researcher. Seduced by the intimacy of Rauschenberg’s handwritten statements or letters from friends and collaborators, one may initially overlook less glamorous documentation of operations and activities with less obvious visual appeal, such as unrestricted financial records. However, items such as receipts, invoices, and other forms of transactional records are rich in evidential value and important pieces of Rauschenberg’s story are told through the archives.

The significance of the information gleaned from items like receipts and proofs of purchase varies depending on the interpreter’s research and focus, but even the smallest details provide clues that can shape the interpretation of the artist’s life and work. The places, dates, itemized purchases, names, and notes or marginalia recorded by these artifacts enhance or, conversely, problematize art historical or biographical narratives by situating Rauschenberg, artworks, projects, and more within a broader context.

The following is a selection of receipts and ephemera in the Robert Rauschenberg Papers that exemplify the research value of these materials. These slips, scraps, and stubs variously illuminate aspects of Rauschenberg’s involvement in key projects, offer insight into his creative process and studio operations, and shape our understanding of Rauschenberg as an artist, collaborator, friend, and human being.

Projects: NASA Art Program

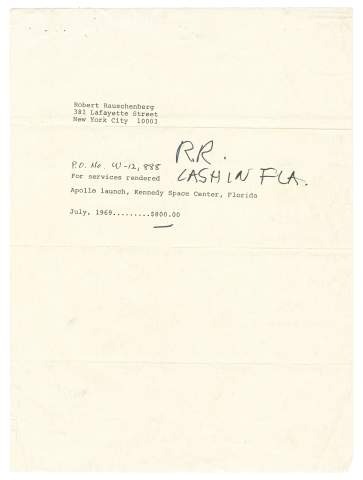

The NASA Art Program was founded in 1962 to enrich the historical record by commissioning American artists to witness and document firsthand the United States’ achievements in space through the creation of unique artworks. As Dr. H. Lester Cookie, Curator of Painting at the National Gallery of Art, explained, “NASA has a mandate to keep the public informed about the space program, and a work of art can have meaning to a segment of the public not reached by any other means.” In 1969, NASA extended an invitation to Rauschenberg to attend the Apollo 11 launch from Cape Kennedy, Florida, and he eagerly accepted. In response to this momentous event–the first flight to land humans on the Moon–Rauschenberg began his lithographic series Stoned Moon (1969–70), of which Sky Garden (1969) is often considered to be the exemplar edition.

The purchase order describes Rauschenberg’s “artist services” to be rendered in exchange for $800, the typical stipend paid to artists for their contribution to the program. An amendment to this invoice, as well as a letter dated April 11, 1969 from NASA administrator James Dean, suggests that this April 7 purchase order merely formalizes Rauschenberg’s participation, rather than definitively assigning him to the May 1969 Apollo 10 launch. The following year, Dean wrote to Rauschenberg, “Before a check can be sent, I am told, we need a note from you saying something like ‘For services rendered - Apollo launch, Kennedy Space Center, Florida, July 1969…$800.’ If you will send this to me I’ll see that your check is sent right away.” Rauschenberg apparently followed Dean’s advice, and alongside this letter researchers can find a typed note from Rauschenberg with exactly this language and reference to the number of the original purchase order.

Sky Garden (Stoned Moon) (1969) is on display now in Robert Rauschenberg: Celebrating Four Decades of Innovation and Collaboration at Gemini G.E.L. (New York and Los Angeles), as well as in Five Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly at Museum Ludwig, Cologne. A new publication, The Ascent of Rauschenberg: Reinventing the Art of Flight, by Carolyn Russo (Smithsonian Books, 2025) also examines letters, receipts, and other archival materials to situate Rauschenberg’s relationship with James Dean and the NASA Art Program within the context of his lifelong fascination with space and flight.

Art Materials: Fabrics

In the mid-1970s, Rauschenberg began an era of experimentation with textiles, resulting in the Hoarfrost (1974–76) and Jammer (1975–76) series. Both series are defined by the use of silks, cottons, and other delicate fabrics, often incorporating commonplace materials such as rope or twine, paper bags, or cardboard. Rauschenberg applied the solvent transfer process to the Hoarfrosts, resulting in gauzy, ethereal hangings with free-associative, transferred images that one reviewer described as like “looking through ice crystals diffused on a windowpane” (Time, January 27, 1975). In contrast, the brightly colored Jammers are largely devoid of representational imagery and often comprise sewn panels of monochromatic cottons or silks. Like the Hoarfrosts, they hang on the wall and feature objects such as rattan poles, string, or tin cans. If the Hoarfrosts evoke a frosted window, the Jammers’ title and form allude to the sails of “windjammers,” or multi-masted ships.

The Jammers were materially inspired by Rauschenberg’s trip to Ahmedabad, India, in May–June 1975, where he stayed at the Sarabhai family estate. Rauschenberg was fascinated by the rich history and traditions of the textile artisanry centered in the area, and with the Sarabhais he explored many of the Khadi (handspun or handwoven cloth) shops and textile markets, examining heaping displays of fabric and purchasing bolts for later use. In her oral history, Asha Sarabhai recalls Rauschenberg’s fondness for Khadi cottons and silks, noting that several of the materials used in Jammers “came from the Bengali saris, which had a main body of one color and often a border of another color.

Not all of the vibrant cloth comprising the Jammer works was sourced from India. A review of receipts in the Business Records from these fruitful years reveals some of the artist’s domestic sources as well, such as Jerry Brown Imported Fabrics in New York. Although the astute researcher can assess patterns of spending and interpret order details, it is impossible to know definitively whether these purchases ended up in Hoarfrosts, Jammers, or became a new bedspread in Captiva. At least one receipt is stapled to a note describing the purchase as “fabric for artwork,” and the arrangement of the invoices among the studio’s financial records provides another clue as to their intended use. Regardless, these receipts offer not only a glimpse at Rauschenberg’s color and fabric choices–white, blue, red, gold; silk, satin, taffeta, organdy (informing later preservation and/or conservation approaches)–but also traces of the New York textile industry as it was half a century ago.

A selection of Hoarfrosts and Jammers, including Mirage (Jammer), are currently on display at The Menil Collection, Houston as part of the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s.

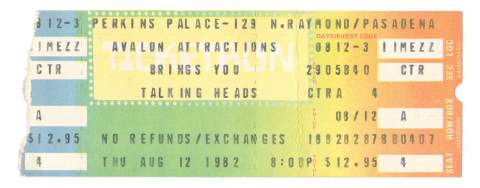

Events: Talking Heads

Not all proofs of purchase document Rauschenberg’s art practice or studio-related finances. The Robert Rauschenberg Papers also contain materials that enable insights into Rauschenberg’s personal interests and tastes, from food preferences to travel plans, clothing and music. Items such as receipts, ticket stubs, and pieces of correspondence can be used in tandem with calendars, schedules, and correspondence to provide evidence of his activities and enrich the record of Rauschenberg as a person.

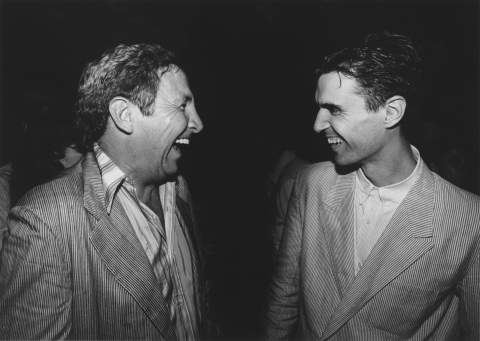

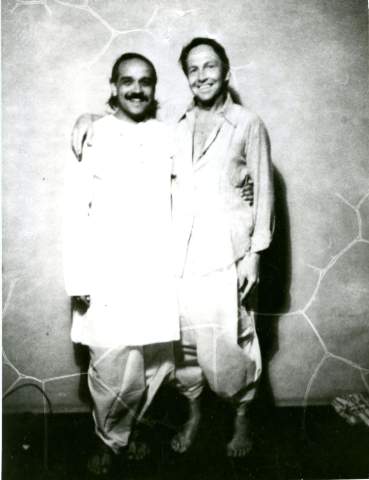

The below ticket stub from the Rauschenberg papers provides a compelling, but incomplete, picture of Rauschenberg as a music fan. When considered with other archival materials, however, we can confidently conclude that Rauschenberg was in fact present–and backstage–at the Talking Heads show, even if we don’t know for sure whether he danced to “Psycho Killer.” A detailed August 1982 calendar page included at the top of this post clearly places Rauschenberg in Los Angeles that week, where he spent time at the print studio Gemini G.E.L., his friend Wolfgang Puck’s restaurant Spago, the pool at “the Chateau” (likely Chateau Marmont), and the home of a man named Gil. The August 12 entry confirms Rauschenberg’s attendance at the concert in Pasadena. Additionally, a letter dated September 9, 1982, from Jeff Gold–assistant to A&M Records President Gil Friesen (the “Gil” referenced in the calendar)–notes, “We’re always looking for the excuse to catch another Talking Heads show.”

The following year, Rauschenberg contributed an original design for a limited edition LP of the Talking Heads’ Speaking in Tongues (for which he won a Grammy), and photographs depict Rauschenberg and David Byrne together at a New York concert in summer or fall. Together, these disparate pieces illustrate the start of Rauschenberg’s professional and personal relationship with David Byrne, who would become a lifelong friend.

Check Your Receipts

These pieces of ephemera comprise only a fraction of the extensive documentation held in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives’ open collections, and while the value tied to their initial function (administrative, operational, etc.) might have been short-term, their value within the archives is anything but ephemeral. As discrete items, their significance and informational worth may vary depending on the ever-turning kaleidoscope of research interests: meaningless to one researcher, crucial evidence to another. However, placed in relation to the other archival materials in the collection, these small, ephemeral bits and pieces add depth and substance to the study of Rauschenberg and innumerable questions yet to be defined.

Interested in researching in the archives? To learn more about our collections, explore the finding aids on our website and email archives@rauschenbergfoundation.org.