Robert Rauschenberg designing a unicorn costume for his sister Janet for a Mardi Gras celebration, modeled by fellow student Inga (Ingeborg) Lauterstein at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, ca. 1949. Photograph Collection. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York. Photo: Trude Guermonprez

A Passion for Fashion: 100 Years of Rauschenberg's Fabric Artworks and Costume Designs

Robert Rauschenberg’s path into fine art started not in a studio, but on the stage. As a teenager in Port Arthur, Texas, he sketched and sewed costumes for school plays. Just a few years later, on the GI Bill, he enrolled as a fashion major at the Kansas City Art Institute. This early training with fabric was just the beginning. Throughout his career, Rauschenberg continued to embrace the sumptuous, malleable qualities of textiles and fabrics both in his costume designs for dance companies and in his innovative artworks.

On the heels of New York Fashion Week and the Foundation’s collaboration with designer Jason Wu for his Spring 2026 “Collage” collection (read more about that here), we are taking a look at Rauschenberg’s use of fabric in art and his fashion designs. See it up close in Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s at The Menil Collection in Houston (September 19, 2025 - March 1, 2026), and catch his iconic sets and costumes live in Dancing with Bob: Rauschenberg, Brown and Cunningham Onstage – now touring across the United States.

In the late 1940s, Rauschenberg had just been honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy and was piecing together a living through odd jobs. In early 1947, he moved to Kansas City with Pat Pearman, an assistant to the designer at a Los Angeles-based swimsuit company. Upon arriving in Kansas City, Rauschenberg changed his name from Milton to Bob (subsequently Robert) after considering the most common names he could think of. A fashion major at Kansas City Art Institute, he threw himself into sketching designs and taking art history courses. At the same time, he saved to pursue further studies at the Académie Julian in Paris, the Art Students League in New York, and Black Mountain College in North Carolina. His Black Mountain College application reveals just how wide-ranging his early career had already been, listing jobs in set design for United Film, advertising art, and hat design and fabrication “for fabric shows for Nelly Don Garment Co.” in Kansas City. Once at Black Mountain, he would study textile construction with two masters of the discipline, Anni Albers and Trude Guermonprez.

By the mid-1950s Rauschenberg was producing the artworks that would jumpstart his career: the Combines (1954–64), three-dimensional artworks that blurred the lines between painting and sculpture, built with everyday items, discarded objects, and so much fabric. “A pair of socks is no less suitable to make a painting with than wood, nails, turpentine, oil and fabric,” he famously declared, signaling his embrace of humble materials. Rauschenberg linked this practice to his mother: “I was embarrassed all through school by the fact that she made all my shirts. I appreciated the fact that she did it, but she did it with remnants, the smallest pieces of fabrics… People would come from all over to have her lay out a pattern because they had a piece of fabric and she could always salvage whatever it was that they had and make it fit… That collage instinct, the reusage of things, and now in this case, try to make this into a piece of real art… comes from my mother.” Not only did Rauschenberg’s Combines collapse boundaries between fine art categories, they also bridged into the performance world. The first fully free-standing Combine he created, Minutiae (1954), shares its title with the Merce Cunningham dance performance for which it was the set.

Months before Rauschenberg created Minutiae for Cunningham’s eponymous work, he designed the set and costumes for Paul Taylor’s choreographic debut Jack and the Beanstalk, jumpstarting a creative partnership that resulted in twelve collaborations between 1954–62. Rauschenberg simultaneously provided sets, costumes, and lighting design for Merce Cunningham, even joining the Cunningham Dance Company on its 1964 world tour. For over 50 years, Rauschenberg continued to explore his passion for fashion as a costume designer for Taylor, Cunningham, Trisha Brown, and Viola Farber. As dancer Deborah Hay recalled in her oral history: “Costuming, props, sets… he loved the challenge of making things from nothing.”

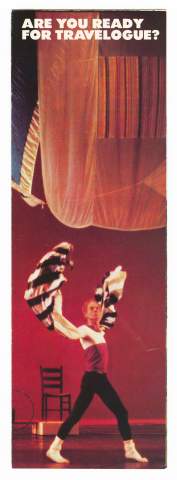

After their collaborations paused in the mid-1960s, Rauschenberg and Cunningham came together in 1977 forTravelogue, with Rauschenberg designing both the décor and costumes. Dancers first appeared in bright leotards, seated on chairs affixed to Tantric Geography—a set made with vibrant, suspended fabrics, wooden platforms, metal bicycle rims, and other found materials. Throughout the performance, these simple costumes were embellished with color-wheel fans, fluttering banners, flags, scarves, and even tin cans, erupting in a vibrant kaleidoscope of colors and movement that echoed the birdsong in John Cage’s original score, “Telephones and Birds.”

Soon after reuniting with Cunningham, Rauschenberg also revived his partnership with longtime friend Trisha Brown, a fellow member of the Judson Dance Theater collective (1962–64). He went on to design what Brown referred to as the “visual presentation” (sets, costumes, and lighting) for her performances Glacial Decoy (1979) and Set and Reset (1983), among other works. In contrast to the bright colors and changing silhouettes of the Travelogue costumes, the Glacial Decoy costumes were quieter. The May 1979 premiere in Minneapolis featured loose, three-piece costumes in muted tones, thereafter superseded by the elegantly diaphanous, A-line dresses that are still used in performances today. For his Set and Reset costume design, Rauschenberg used similarly translucent, mesh fabric–this time silkscreened with his own photographs of New York City in cool grays and black and white. This year, the Trisha Brown Dance Company and Merce Cunningham Trust highlight Travelogue and Set and Reset in a national tour that premiered at the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina in June.

The artist resisted what he called “fixedness of a painting.” In the 1970s, a glimpse of cheesecloths, used for cleaning presses, swaying in a printshop inspired him to create fabric works which undulate with passing air currents. The resulting Hoarfrost series (1974–76) featured imagery transferred onto gauzy, overlapping rectangular panels of textiles. Soon after, in his Jammers (1975–76), he paired rigid rattan poles and bold silky fabrics, exploring boundaries between hard and soft. This turn to fabric was fueled in part by his May 1975 trip to a textile center in Ahmedabad, India, where his son Christopher, who accompanied his father to India, recalled him as being “just amazed at the colors. A new sense of fabric came to him there.”

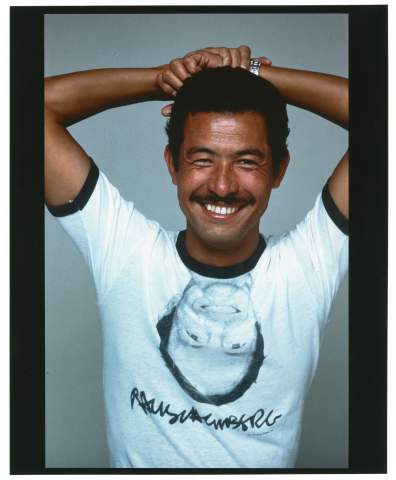

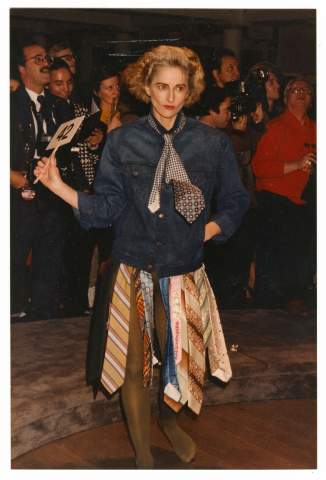

In addition to his own artmaking practice, Rauschenberg was a passionate advocate for artists and the creative community at large, forging friendships with creatives as diverse as Issey Miyake, Sharon Stone, and Merce Cunningham. In September 1970, he founded Change, Inc., a non-profit organization dedicated to providing emergency support to artists in need. He often created editions and posters to benefit various causes, and even designed clothing for benefits–like his take on the jean jacket pictured below (modeled alongside designs by visual artists such as Andy Warhol and Keith Haring as well as Yves Saint Laurent, Hermès, and other haute-couture fashion designers).

Between 1984 and 1991, Rauschenberg traveled to ten countries outside of the United States as part of his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI), a project designed to foster cross-cultural dialogue through art. Among the works he produced for this initiative is the series of Samarkand Stitches (1988), created in advance of his ROCI USSR exhibition in Moscow the following year. Each piece in the series is a double-sided, sewn tapestry. Although published by Gemini G.E.L. as part of an edition, every work is unique, shaped by the variations in the hand-woven fabric Rauschenberg sourced during a research trip to Uzbekistan. The series combines brightly dyed and patterned ikat silk with textiles that Rauschenberg acquired locally in the U.S. and to which he applied screenprinted imagery from photos he took in what was then the Soviet Union. A work from the Samarkand Stitches series is currently on view at the Foundation’s headquarters in New York. Learn more on the Foundation’s free digital guide through Bloomberg Connects and/or RSVP to visit during one of our upcoming open Saturdays.

Inspired by the dazzling range of colors and patterns of textiles he encountered while traveling, Rauschenberg continued to explore the relationships between his own images and textile techniques. In 1995, he created the Faux-Tapis series—monumental, ten-foot-long panels made from mounted fabric printed with images drawn from his photography. Stacked one above another, they fill a wall like bold, “fake tapestries.” Some of the fabric traces back to 1983, when Rauschenberg commissioned batiks at a workshop in Sri Lanka.

Even when fabric was not his medium of choice, it often appeared in his imagery. Photographs of dangling laundry or fabrics hung to dry recur throughout Rauschenberg’s work, once again linking everyday life to art. Such works from the 1990s show how quick he was to embrace new technology: just as digital printing and image-editing software emerged, he was experimenting with high-resolution printers. What is now standard practice was, then, radically new.

Over the course of Rauschenberg’s six-decade career, his fascination with fashion found outlets in his costume design and his textile artworks. Despite being called a forerunner of essentially every postwar movement since Abstract Expressionism, he identified himself with none of them. An artist who was as vibrant and malleable as the fabrics he used, Rauschenberg constantly worked across disciplines to keep viewers and collaborators on their toes. In a 1977 Artnews interview, Rauschenberg said, “I don't really trust ideas—especially good ones. Rather, I put my trust in the materials that confront me, because they put me in touch with the unknown.”

Quotes from:

Rauschenberg, statement in Dorothy C. Miller, ed., Sixteen Americans, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959), p. 58.

Interview with Mary Lynn Kotz, February 21, 1998. Mary Lynn Kotz papers. Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York.

The Reminiscences of Deborah Hay, 2014. Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. Conducted in collaboration with INCITE/Columbia Center for Oral History Research. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives. https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/oral-history/deborah-hay

Billy Kluver, On Record: Eleven Artists 1963 (New York: Experiments in Art and Technology, 1981) pp. 44-45.

John Gruen, "Robert Rauschenberg: An Audience of One," Artnews (New York) 76, no. 2 (Feb. 1977), p. 48.