Robert Rauschenberg: Spreads, 1975–83 at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London

First UK Exhibition Dedicated to Rauschenberg's Major Series of Spreads, Inspired by "Autobiographical Feelings," After His Celebrated Combines

“They are more like ideas than objects―reels of association run through the projector of a mind unusually sensitive to the up-and-down jangles of modern life.” -Thomas B. Hess

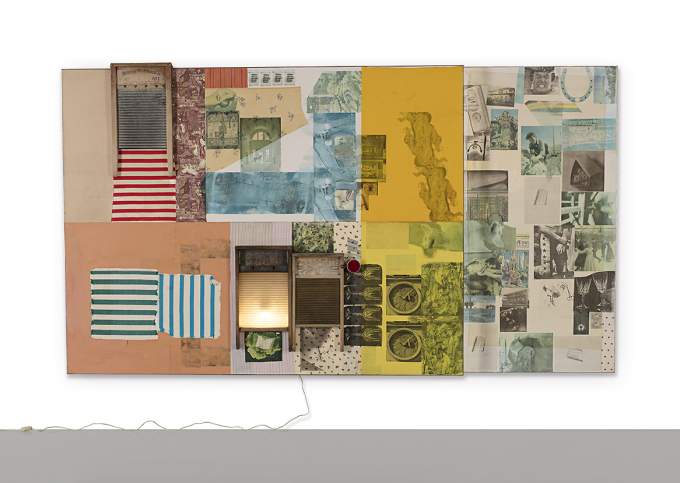

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London, together with the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, presents the first UK exhibition dedicated to the American artist’s remarkable Spreads, a series that occupies an important position in his oeuvre. The large-scale Spreads (1975–83) encapsulate many of Robert Rauschenberg’s best-known motifs and materials. Twelve key works from the series―the largest of which stretches to over six metres wide―will go on view at Ropac’s London gallery from 28 November 2018. An integral series of paper collages from the same period will also be exhibited, incorporating fabrics and techniques that relate to the Spreads series.

One of the most influential artists of the post-war period, Rauschenberg revolutionised the picture plane with his hybrid painting-sculptures, created through the innovative inclusion of everyday objects―what he called “gifts from the street”. These Combines (1954–64) marked a watershed moment in the history of post-war art, redefining and expanding the boundaries of what could be considered an artwork. It was in 1976, as the artist prepared for an important mid-career retrospective, that Rauschenberg found inspiration for his new Spreads series. The exhibition, which opened at the National Collection of Fine Arts (now Smithsonian American Art Museum) in Washington, D.C., offered Rauschenberg the opportunity to revisit works he had not seen for up to 25 years, prompting what he described as “autobiographical feelings”, and imparting a retrospective aspect to his new works.

In these Spreads, “classic Rauschenberg” motifs from his object-laden Combines resurfaced, including tyres, doors, bedding, ironing boards, mirrors, electric lights, ventilators, metal traps, images of exotic animals, bird wings, umbrellas and parachutes that recalled those in his acclaimed 1963 performance piece Pelican. Yet these fulcrum works were also informed by the materials and images of his silken Jammers (1975–76) and solvent- transfer Hoarfrosts (1974–76), whilst prefiguring his later metal works from the 1980s–90s, such as the Shiners (1986–93), Urban Bourbons (1988–96) and Borealis (1988–92).

“Rauschenberg is a painter of history―the history of now rather than then.” -John Richardson

Rather than a purely retrospective exercise, the development of his Spreads is also suggestive of a more complex relationship between past and present, integrating not only elements from his earlier work but also reflecting changes in his life, his practice and in contemporary art at the time. Rauschenberg’s use of fabric colour blocks in his Spreads not only represented a shift in his colour palette from the urban experience of New York to the bright oranges, pinks and yellows of life in Florida, but also engaged with recent artistic developments such as Colour Field painting and Minimalism, incorporating references to a new generation of artists.

In the works directly preceding the Spreads, particularly his Cardboards (1971–72) and fabric Jammers, Rauschenberg had eliminated imagery in favour of a sparser visual language focused on materials. After the relative minimalism of these series, the excesses of the Spreads marked a triumphant return to imagery. “In recent years this artist has left everything out, the Jammers being the prime example,” wrote critic William Zimmer of the Spreads exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1976. “Rauschenberg has put everything in again. Replacing the raucous gestural passages that mark his early work are tighter passages [. . .] Although there is once again a lot going on, it is cleaner. The whole earth catalogue, from arcane imagery to very public signs, is back and actual pendant objects reappear―a rubber raft, chairs, tyres, electric lights.” The pendant objects that appear in the works on view include lightbulbs, umbrellas, mirrors, a metal bucket, split tyre, and even an oar. These are affixed to wooden panels and collaged with fabric scraps and solvent transferred media images drawn from contemporary newspapers and magazines.

Asked about his use of the term “Spread”, Rauschenberg responded that it meant “as far as I can make it stretch, and land (like a farmer’s ‘spread’), and also the stuff you put on toast”. This term also clearly refers to the scale of the works, with their large, fabric-covered supports that stretch across the wall. The first work in the series, Yule 75, was created in December 1975 and cut into 56 irregular pieces that Rauschenberg distributed to his friends as Christmas gifts. Another of the earliest, Rodeo Palace (1976) was commissioned for the exhibition The Great American Rodeo at the Fort Worth Art Museum, and later included in Rauschenberg’s 1976 retrospective. The same expansiveness and breadth of vision characterises the works included in this exhibition, with the largest work, Half a Grandstand (1978), stretching to over six metres.

The accompanying exhibition catalogue with an essay by Elisa Schaar, published to coincide with the exhibition opening, is the first publication devoted to Rauschenberg’s Spreads.

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac has represented the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation since April 2015.